Start your Ballina story on real ground

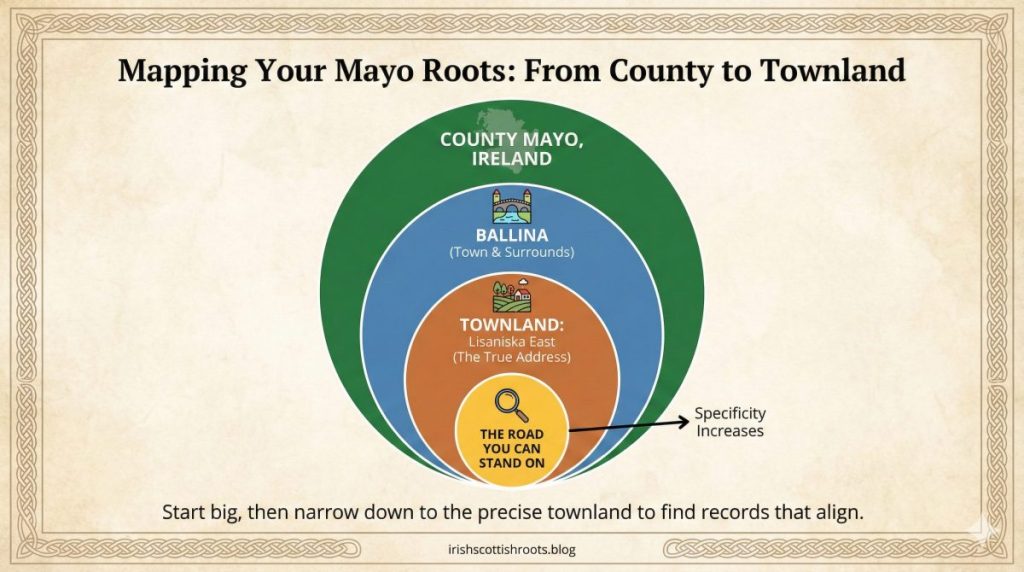

When you begin tracing family in County Mayo, it often starts with a single word: Ballina. It feels specific until you arrive and realize how much ground that name actually covers. County Mayo genealogy only becomes productive when you move from county to town. Then, you must proceed from town to townland. Finally, it becomes clear only when you find a road you can stand on.

For many families, that road leads to Ballina and into the surrounding countryside. This article follows a heritage trail you can walk. It also shows you how to use county mayo genealogy records the same way along the route.

Put Lisaniska East on the map before you book anything

If your research points to Lisaniska East, you are already ahead of most first-time Mayo researchers. Lisaniska East is a townland, not a neighborhood or a village, and townlands are the true addresses of rural Ireland.

Before planning a trip, write one clean location line in your notes: Lisaniska East townland, near Ballina, County Mayo, Ireland.

From there, layer in parish, registration district, and nearby townlands. This step feels small, but it is where Mayo research starts to behave. Records that once looked scattered begin to line up.

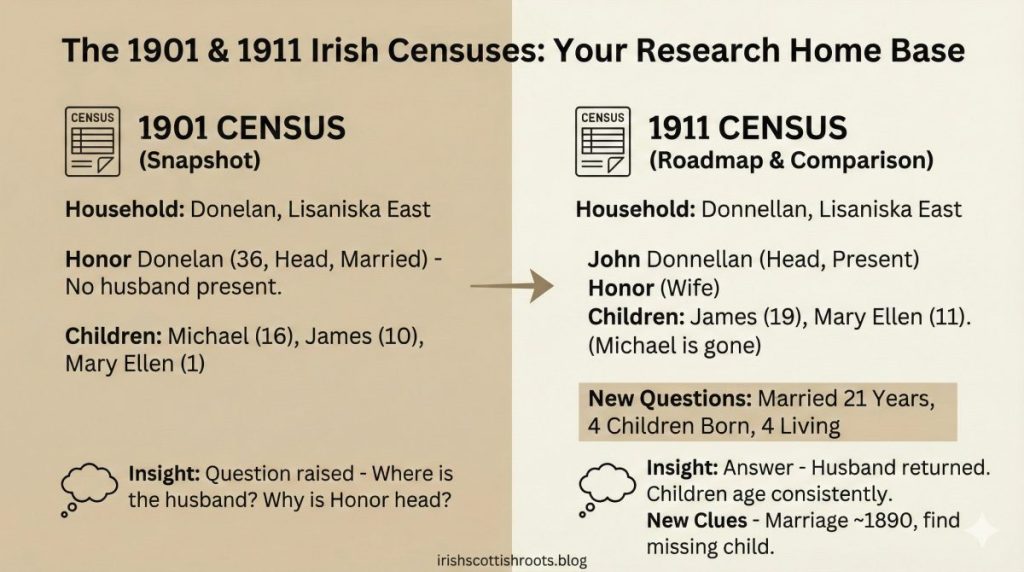

Stop: Use the 1901 and 1911 Irish censuses as your home base

Before stepping into a churchyard or opening parish registers, pause with the 1901 and 1911 Irish censuses. For Ballina research, these two returns are often where county mayo genealogy shifts from guesswork to proof.

In Lisaniska East, the census does more than list names. It anchors a family to a house, a townland, and a community. That is the difference between visiting Mayo and understanding it.

What the 1901 census gives you immediately

In 1901, the author’s great grandparents appear clearly in the records. A household in Lisaniska East shows Honor Donelan, age 36, listed as head of household. She is married, Roman Catholic, and living with three children: Michael (16), James (10), and Mary Ellen (1). There is no husband present.

That single entry does a surprising amount of work for you.

First, it replaces a vague family story about “Ballina” with a precise place. Lisaniska East becomes the foundation for every record that follows.

Second, it introduces a question worth solving. Honor is married, yet she is running the household alone on census night. In Mayo, that absence does not automatically signal death. It often points to seasonal labor, estate service, or temporary work away from home.

Third, it establishes a working family structure. The children’s ages suggest birth years, spacing, and a likely marriage window. Those details quietly guide every later search.

Why comparing 1901 to 1911 matters

The real insight comes when you follow the same household forward.

In 1911, the family appears again in Lisaniska East. This time, John Donnellan is present and listed as head of household. Honor is listed as his wife. James and Mary Ellen are still at home. Michael is gone.

That comparison answers the question raised in 1901. The husband was not missing from the family. He was missing from that night.

The children line up almost perfectly across the ten-year gap. James ages from 10 to 19. Mary Ellen ages from 1 to 11. That kind of consistency allows you to trust you are following the same family. This trust holds even when spellings drift or ages wobble.

Using the 1911 census to move backward with confidence

The 1911 census adds questions that change how you plan your research. Married women were asked how many years they had been married. They were also asked how many children they had borne and were still living.

In this household, Honor reports 21 years married, four children born, and four children living.

That answer creates direction. A marriage around 1890 becomes the next target. Four children should exist in the records, not just the three you already see. One child is missing from your picture, and the census tells you that child was alive in 1911.

This is where the census stops being a snapshot and starts acting like a roadmap.

What you should check next to flesh out the census

The census tells you who was in the house on one night. It does not tell you how the family formed, where it came from, or what happened between census years. To answer those questions, you build outward in layers.

Start with civil marriage records

Once the census shows a married couple, your next stop should be the civil marriage record.

A civil marriage can confirm:

- Full names of bride and groom

- Ages or full-age status

- Occupations and residences at the time of marriage

- Fathers’ names and occupations

- Witnesses, who are often relatives or neighbors

In a case like this, the 1911 census points you to a marriage around 1890. That record often becomes the document that links two generations together.

Add Catholic parish marriage records

Catholic parish registers are not duplicates of civil records. They often add context.

A parish marriage can:

- Confirm which parish the family actually used

- Reveal alternate spellings

- Identify witnesses who later reappear as baptism sponsors or census neighbors

In rural Mayo, parish boundaries and civil boundaries do not always match neatly. Seeing where a marriage was recorded helps explain later baptism and burial locations.

Use civil birth records to test census ages

Census ages are approximate. Civil birth records give you dates.

For each child listed in 1901 and 1911, birth registrations help you:

- Confirm birth order

- Identify age drift in census returns

- Find children implied by the 1911 “children born” count

In this household, the census tells you to look for four children. Birth records help you account for all of them.

Read Catholic baptism records for family networks

Baptism records are where Mayo genealogy comes alive.

Beyond parents and dates, baptisms list sponsors. Sponsors are rarely random. They are often siblings, cousins, or in-laws. When the same sponsor names appear repeatedly, you are seeing a kinship network the census alone cannot show.

This is how you separate families with the same surname living in neighboring townlands.

Check civil death records for disappearances

When someone vanishes between census years, death records help you confirm whether that absence is permanent.

Even when no death is found, the search itself matters. A missing death record strengthens the case for emigration or relocation rather than assumption.

Use graveyards carefully

Gravestones and burial registers support your work, but they are not complete. In Mayo, many burials were never marked.

When stones do exist, they can:

- Confirm family groupings

- Show local spellings

- Reveal surname clusters that mirror census neighborhoods

When visiting graveyards near Ballina, photograph neighboring stones as well. Those names often reappear later as witnesses, sponsors, or neighbors.

Keep land records in view

Once a census ties a family to a townland, land records help you follow them across decades.

Land valuation records and later revisions show:

- Who held land

- When a name appears or disappears

- Whether a holding passed to a son

- Whether a family stayed rooted to the same place

This is especially important in Mayo, where families often remained in the same townland even when individuals worked elsewhere.

Always circle back to the census

After each new record, reread the census.

With fresh information, details that once seemed minor start to matter. A neighbor becomes a witness. An occupation explains an absence. A house location aligns with a land holding.

This back-and-forth is how census records become anchors rather than isolated facts.

Once you have worked through census returns, identify which civil and church records matter most. This step is crucial. You need to take that focused research back into the local landscape. This is where County Mayo’s heritage and genealogy centers become part of the trail itself, not just a backup plan.

Heritage and genealogy centers that support County Mayo genealogy research

Local heritage centers deepen your census findings

Once you understand which records matter most, local heritage and genealogy centers in County Mayo can help you move faster and avoid blind searches. In Ballina and across North Mayo, these centers hold local indexes, gravestone transcriptions, estate references, school notes, and parish material that rarely appears online. Just as important, they offer staff knowledge rooted in place. A visit to Mayo North Heritage Centre in Ballina is especially useful when your research is already grounded in a specific townland like Lisaniska East. County-level resources connected to Mayo County Library add further depth through historic newspapers, maps, and local histories. Together, these sources help you place census households within the real social and geographic fabric of Mayo.

Prepare so your visit pays off

Heritage centers work best when you arrive prepared. Before you visit, book research time if required and send a short email outlining your focus. Include surnames, known name variants, townland, parish, and an approximate date range. Instead of asking for everything connected to a surname, ask how families in a specific townland or parish cluster appear in local sources.

Before you walk through the door, make sure you have the following ready:

- Your exact townland, not just Ballina or County Mayo

- Full names, known spelling variations, and approximate dates

- Details from the 1901 and 1911 censuses, including house numbers if available

- The parish or likely parishes connected to the family

- One clear research goal, such as identifying a marriage, locating a missing child, or confirming a landholding

- Confirmation of whether appointments or advance requests are required

- Printed notes or offline access to your research

Arriving prepared signals that you are doing focused research. When staff can see exactly what you are trying to solve, they are far more likely to point you toward sources you would never find on your own.

Walk Ballina with County Mayo genealogy records in mind

Once the census work is done, Ballina itself makes more sense. Standing along the River Moy, you can see how the town draws surrounding farmland toward it. That geography explains why families stayed rooted even when individuals came and went.

This is not sightseeing filler. It is context that sharpens interpretation.

St Muredach’s Cathedral and Catholic continuity

A visit to St Muredach’s Cathedral reinforces how central Catholic parish life was to record creation. Baptisms and marriages are where Mayo families leave their clearest paper trails.

Pay attention to sponsors and witnesses here. In Mayo, records speak to each other if you let them.

A short drive north for deeper context

A heritage loop toward Killala Bay adds texture without leaving the research framework. Places like Rosserk Friary remind you that families lived within landscapes shaped over centuries.

Pun, because Mayo research deserves one: this is where your family tree stops wandering and finally puts down roots.

Bringing it all together

The goal is not to say you visited Ballina. The goal is to say you connected a family in Lisaniska East to a parish. Then, you connected them to a household and a community network. This connection holds up under scrutiny.

That is the heart of county mayo genealogy. Travel gives your research meaning. Method gives it results.

Sign Up

Subscribe to irishscottishroots.blog for more Mayo heritage trails that combine travel, records, and real research strategy.

Internal reading on irishscottishroots.blog

You may also enjoy: Ballina family visit – a homecoming in Mayo

More to explore next:

- Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland – A Genealogist’s Guide

- Belleek Castle Overnight: Dinner, Rooms, and Walks

- Ballina, County Mayo – Family Roots and Castle Legends

- Old Family Photographs and an Unexpected Genealogy Adventure

- Bridging Generations: Memories of the Covey-Donlan Connection

All images in this article were generated by Google Gemini.

Discover more from Irish Scottish Roots

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.